Transhuman Parenthood

Sebastian Sethe

page 2 of 4

My second conclusion is that maturity is not a binary question either. There are degrees of maturity. We are not asking whether something is smart enough to be a person, but we are considering its development in all of these categories of maturity.

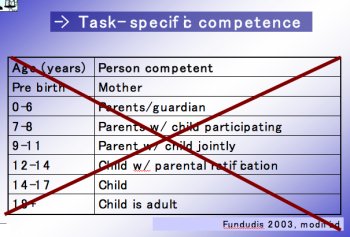

In humans, these different aspects co-evolve, so we tend to equate chronological age with maturity. Image 2 is an example from Fundudis [1] considering the legal recognition of autonomy in refusal of treatment decisions.

Image 2: Legal Recognition of Autonomy By Age

Yet even common law has recognized that age alone is an insufficient indicator for such questions, and this very table is testament to that.

At 14-years old, there is specific competence, as we call it in the U.K. Children are not old enough to vote at this age, but they are old enough to make their own independent decisions on life-and-death medical matters. Thus, strictly a linear model does not work.

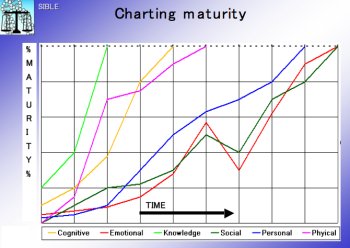

In Bioethics, we are certainly moving towards recognition of task-specific competence. Yet this non-linear maturity is a challenge in humans as well. Image 3 is an example of charting and projecting the relative maturity of a computer-based entity.

Image 3: Charting Maturity

The entity’s mathematical and memory capacity develop very quickly to the human equivalent and probably beyond. Yet in terms of emotional maturity, it takes a bit longer. It might take a while for each of these aspects to equate to a mature human, as we usually consider it.

What is the model that is actually being proposed here? Arguably, the person or the child is no less a person, but we do not endow it with autonomy to make its own decisions on account of its unfinished state. Therefore, the parents are allowed to make decisions by proxy on behalf of the child.

There are several reasons that justify the proxy decision making model. The first reason is the authorship theory. Because the mother and father are the biological authors of the child's genetic makeup, they should also be the authors of the child's early social biography. Thus, the biological relationship is recognized, affirmed, and supported by law.

The second theory relies on what some call evolutionary psychology. Crudely put, because children are our means of promulgating and securing our genetic configuration through time, it is an evolutionary imperative to ensure the well-being of one's children. Thus, biological parents are probably best positioned to be concerned about the best interests of a child. This, in fact, is the thesis which is most closely reflected in actual legal practices. Biological parents, who by direct or indirect declaration, deny that they have the best interest of the child at heart lose their status, if not as parents then at least as legal guardians. Examples where the law relies on this theory range from sperm donation and adoption, to abuse and neglect.

Thirdly, on account of this evolutionary motivation, parents do invest time, labor, discomfort, and resources in fostering the development of a young child and they should be recognized for that. In a way, it is a reward theory. Once again, the parenthood is a boon that the law bestows. If parents conversely fail to produce these investments, their guardianship is revoked.

1. Trian Fundudis; Consent Issues in Medico-Legal Procedures; How Competent Are Children to Make Their Own Decisions?; Child and Adolescent Mental Health (2003); Vol. 8 pp 18-22 (back to top)

1 2 3 4 next page>