All Together Now: Developmental and Ethical Considerations for Biologically Uplifting Nonhuman Animals

George Dvorsky

page 2 of 7

Recent initiatives in Spain and New Zealand seeking to establish legal personhood status for the great apes represent unprecedented steps in the history of the animal rights movement. Great apes are poised to be endowed with rights that have traditionally been ascribed only to humans, a development that would see their promotion from non-persons with property like status to persons with real and enforceable protections. In all likelihood, and though it may take some time, other countries will follow suit.

Image 1: A great ape. ©iStockphoto.com/Jackson Gee

Humanity has been widening its moral purview for some time now. With rights potentially being passed down to the great apes, it can be said that humans are widening both their moral and social circles. This is a trend that will have profound implications for the relationship between humanity and nonhuman animals.

UPLIFT HAPPENS

Nature versus nurture

Biological uplift is one of two major ways in which an organism can be endowed with superior or alternative ways of physical or psychological functioning. Memetic uplift, or cultural uplift, is distinguished from biological uplift in that it typically involves members of the same species and does not require any intrinsic biological alteration to the organism. While biological uplift is still set to happen at some point in the future, cultural transmission and memetic uplift have been an indelible part of human history.

Memetic uplift can be construed as a soft form of uplift. Memes are by their very nature rather ethereal cultural artifacts, whereas biological uplift entails actual physical and cognitive transformation. That’s not to suggest that inter-generational non genetic transfer of information is subtle. Society and culture have a significant impact on the makeup of an individual.

That said, human psychology is powered by genetic predispositions that function as proclivity engines, endowing persons with their unique personalities, tendencies and latent abilities. This is why the environment continues to play an integral role in the development of the entire phenotype. How persons are socialized and which memes they are exposed to determines to a large part who and what individuals are as sentient, decision-making agents. Consequently, people are constrained and moulded in a nontrivial way by their culture-space. Humans have moved beyond their culturally and phenotypically primitive Paleolithic forms owing to the influence of an advanced culturally extended phenotype and the subsequent rise of exosomatic minds and bodies.[1]

An Example of Memetic Uplift

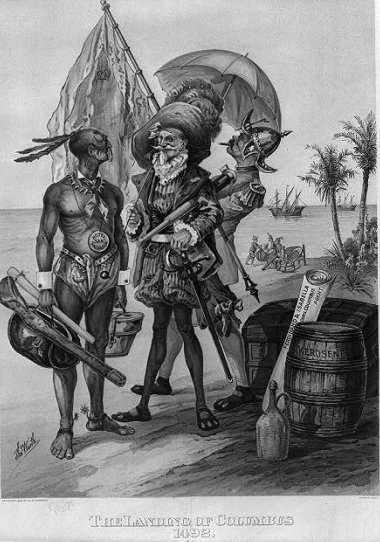

One of the most striking examples of memetic uplift was the colonization of the Americas by the Europeans. From a macrohistorical perspective, the clash of European and indigenous American civilizations was one between a post-feudal monarchist society and a Stone Age culture. The wide technological and cultural gap separating the two societies gave the Europeans a considerable edge in their ability to successfully wage an invasion that resulted in the embedding of their political, economic, and religious institutions on the continent. The Europeans were also proactive about “civilizing” aboriginal peoples -- in some cases forcing them to attend English schools or converting them to Christianity. Today, very few aboriginals, if any, are able to maintain a lifestyle that even modestly resembles life in pre colonial times. The colonization of the Americas resulted in the emergence of an entirely new set of cultures.[2]

Image 2: The landing of Christopher Columbus in America in 1492. Library of Congress c1893 Buek.

Footnotes

1. The exosomatic organ theory of technology was originated by Ernst Kapp (1808-1896) in his seminal book, Grundlinien einer Philosophie der Technik (1877). (back to top)

2. Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, “Atlantic Empires and the Exchange of Cultures,” lecture at the University of Western Ontario, April 2006. (back to top)